There’s no need to make the case for perfection. It speaks for itself. But imperfection may need its advocates and disciples, especially in art, where flawlessness ostensibly lies in the hands of the artist alone. The advocates and disciples call themselves Imperfectionists. They say the beauty is not in spite of the flaws but because of them.

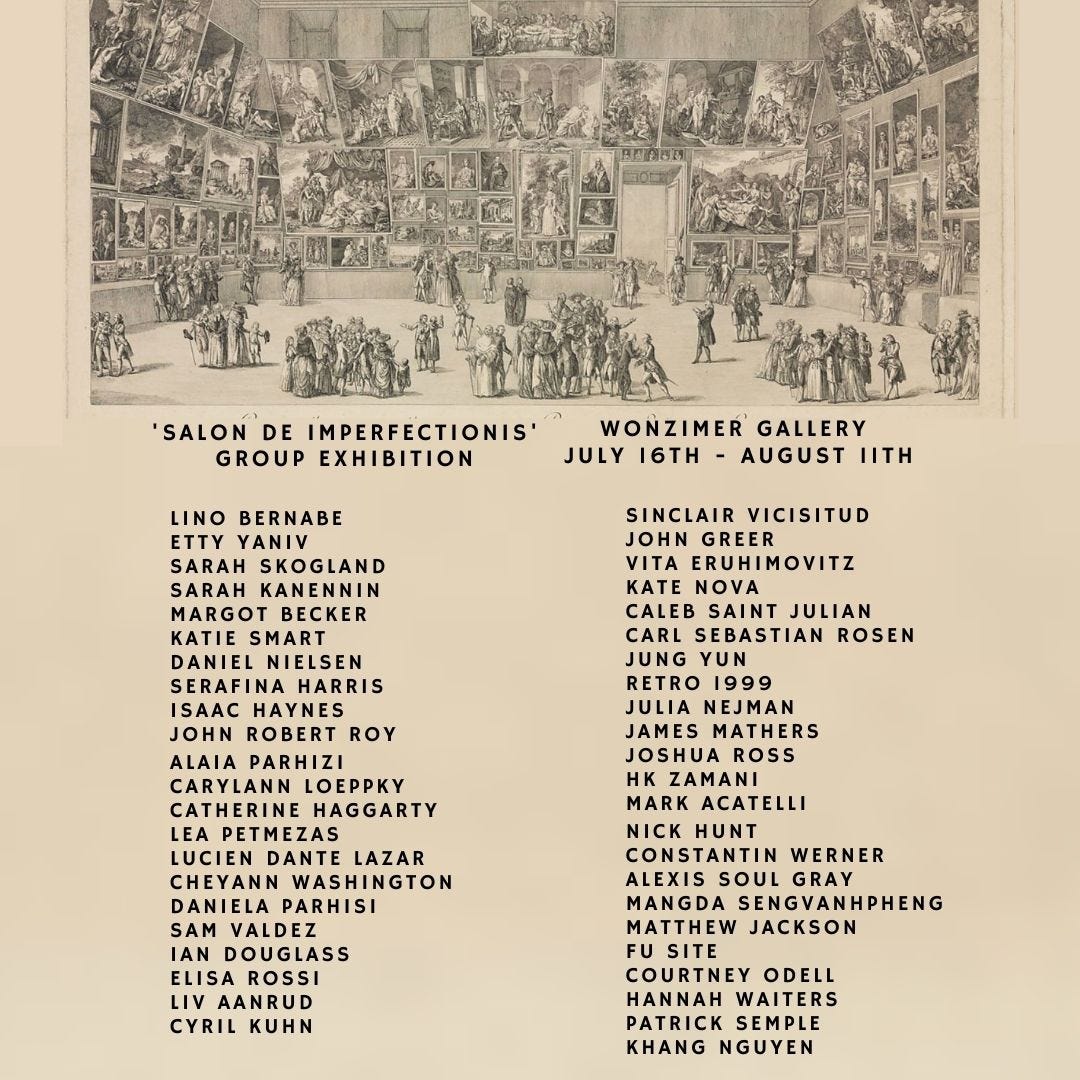

46 Imperfectionists will display work at Wönzimer Gallery’s SALON DES IMPERFECTIONISM in Downtown LA from July 16 to August 11. The idea for Imperfectionism first came to Alaïa Parhizi – painter, musician and co-founder of Wönzimer – in 2014, and he published a manifesto last year. At the show, curators Parhizi and painter/philosopher Lucien Dante Lazar will display work in the style of a 17th/18th century French Salon.

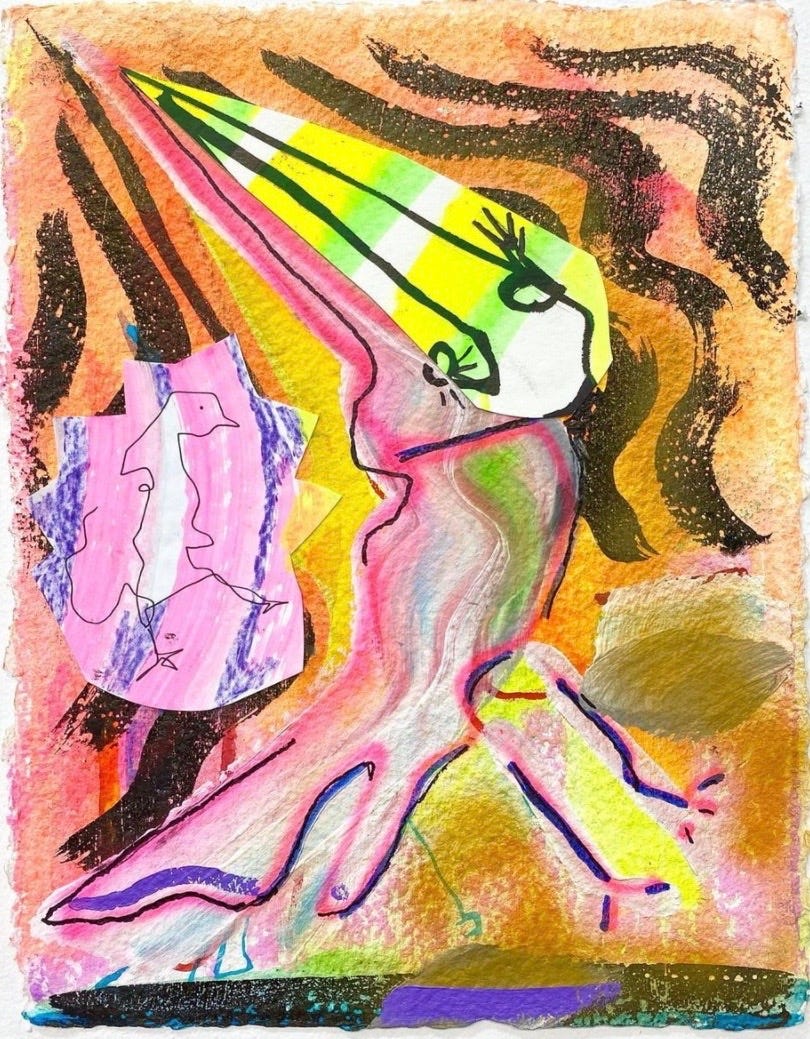

Imperfectionism is an aesthetic philosophy, creative method and artistic movement. The manifesto writes that Imperfectionism “embraces the accidental nature of artistic creation and incorporates apparent mishaps into the art … Rather than pioneering a specific artistic aesthetic or medium, Imperfectionism defines a method of self-knowing through the arts, where intuitive decision-making, raw expressive impulses and imaginative self-discovery are the foundational tools. The Imperfectionists recognize the beauty in flaws and elevate it to be the sacred elements in their art.”

The movement emerges at a time when artistic communities are at once easier than ever to foster via technology and still nonexistent or hard to find; artists remain isolated and individualistic. It imagines work that connects viewers to the artist through an embrace of the artistic process and it pursues art as a spiritual quest. Though many works in the show are abstract, Imperfectionism is based in embodied phenomena rather than concepts – surprise at one’s own work; the sense of meaning one can feel in the presence of art; the experience of freedom, love and chance. Imperfectionists see perfection as always out of reach, manifesting only in reality or life as a whole, in eternity, God or nature – they attempt to honor our consciousness, the means through which we perceive, interpret, and interact with life’s imperfections. To celebrate imperfections is to pay homage to that which made us imperfect.

There has been a lack of communal ideas in the art world for at least twenty years, Parhizi said. “I haven’t seen many and if there are they’re smaller movements or collectives, mostly focused on the individual artist in the art market and how much money they make,” he said. “It’s very competitive and has lost its community … That’s what I want to bring together with the movement, because it is our similarities that we can relate to, even though we are individuals following our own path in art.” LA based painter Kate Nova, whose work will be in the show, said she was excited to see a manifesto published by someone in the art world, especially in Los Angeles. Through the 20th century, artists joined one another and made work with common themes: Abstract Expressionists, Cubists, Minimalists, and artists who sometimes outlined their aims explicitly as with the Futurists and Dadaists.

“The world was able to pay attention to them more,” Nova said. “It’s not so much about getting famous as an artist – that’s actually what this seems to be working against. It’s more so you want to show your art, you want to get that recognized, you want eyes to see it and people to experience it.”

Imperfectionism, in its search for meaning through the sensory experience of art, stands against the pure conceptualism and cynicism of 1980s postmodernists, Constantin Werner said. Werner is from Munich, an alumnus of the Beaux-Arts de Paris, and his piece for the show “Imperfection, Moonrise” is a reference to “Impression, Sunrise,” the work Monet showed at the Exhibition of the Impressionists in 1874 and which arguably gave the movement its name. Werner said Imperfectionist art is like traditional Persian rugs, deliberately made with mistakes in patterning, an ode to the belief that only God is perfect. The movement also evokes Stuckism, he said, a movement founded in 1999 as a quest for authenticity and the spiritual value of art, a critique of postmodernism and rejection of “anti-art” mentalities.

Parhizi said he takes influence from Japanese wabi sabi aesthetics as old as 16th century tea ceremonies, which find reverence for defects in tea bowls and huts. Flaws are the result of age, mistakes or conscious destruction.1 Like the purposeful breaking of a wabi bowl by teamaster, Imperfectionist artist Julia Nejman said “There’s a want for destruction with Imperfectionism, just to see what may happen pushing your own boundaries.” The movement also follows 18th century British ideas of the picturesque, which values asymmetry, complexity and irregularity. The picturesque finds beauty in architectural ruins and overgrown gardens, beauty which may be lacking in perfect Neoclassical buildings or the well-kept American front lawn. In 1925, Christopher Hussey contrasted the picturesque with the sublime and the beautiful, two other aesthetic ideals. While the sublime has “vastness and obscurity,” and the beautiful has “smoothness and gentleness,” the picturesque has “roughness and sudden variation joined to irregularity of form, colour, lighting, and even sound.”2 Echoing Gay Leonhardt, who wrote in 1985 that one must develop an “eye for peeling paint,” Nejman said “flowers are great but it’s nothing in comparison to the graffiti mural that has torn wallpaper all over it and some exposed brick … difference comes from individuality, and this art is individuality.”

“I don't really believe in the political power of art as much as some other people might,” Imperfectionist Ian Douglass said. “But I believe that it can save your life and it can change your mind and your consciousness and I think that is extremely valuable.” For some artists, Imperfectionism is less about art’s political power than it is about art’s spiritual, psychological and interpersonal power. Werner said identity politics are trending in the art world today, and while galleries have introduced the world to great artists from different cultures – like Kenyan painter Michael Armitage, he said – a focus on identity politics, in its superficiality, may sacrifice art’s ability to universally connect with people emotionally and spiritually. It may be that in 2021 we are hungry for meaning rather than looking to subvert it; political change is less the artist’s job than the responsibility of those in power, too often abnegated. More specifically for artists, it may be that, as Anna Khachiyan wrote, “as long as art remains a prestige economy of the free market — a glitzy barnacle on the side of global finance — it cannot be an effective tool for political change.” Imperfectionism’s devotion is to the individual’s relationship with one’s self, one another and the divine.

Lazar – an Imperfectionist artist, PhD candidate in philosophy, and the Salon’s co-curator – said the art world’s ethos of capitalism, commodity and consumerism have stripped art of an evolutionary impulse. Echoing Lazar’s call for a forward-thinking art, Cheyann Washington, whose work will be in the show on the 16th, said “the whole idea for Imperfectionists is to evolve, and almost accept the changes and the differences within each other, within our art, within societies.” For Lazar, true cultural development through art is only possible if we respect art as art, and not simply as a medium for socio-political insight or dissent. The art must be in love with art, he said. Art cannot be celebrated as a concept because it is not simply a concept. “It’s a profoundly original human activity,” Lazar said. “It has contributed to the evolution of the human being in the most fundamental way.” Imperfection can connect people, he said.

“If we really ask who the human being is, then art will naturally receive the human being’s meaning,” Lazar said. “It will receive the living impulse of the human being and it will become a guide into a deeper awareness of the human being and not just a guide into abstract cultural concepts that may seem alluring and seem woke and seem cutting edge, but really they are not. They are fractions of reality.”

Freedom, love and chance: it was while talking with Parhizi, as well as in the “intuitive spiritual realm of phenomena” entered during meditation, that Lazar said he helped formulate these Three Pillars of Imperfectionism. Nejman said she saw herself “living through art” with these pillars of Imperfectionism before she knew them. “I hope viewers can feel a sense of freedom,” she said. “I think that’s probably the biggest thing … when I perceive their art I just feel open minded. My mind is open, I’m free.” Similarly, Parhizi said he hopes artists find liberation through Imperfectionism, as he did when first making art with the philosophy. “Let me make something without knowing what I’m going to do,” he said, explaining his original thought process. “Slowly I was impressing myself instead of being disappointed, and that was liberation.” Lazar said what makes an Imperfectionist artwork is its incorporation of these fundamental principles.

Freedom, love and chance are phenomena, Lazar said, not just abstract concepts. The same can be said about Imperfectionism. The manifesto writes, “Instead of pursuing a certain outcome, the artists allow themselves to be surprised by their own creation, and satisfied with the outcome because it has surpassed what they could have planned for.” This freeform artistic technique and moment of surprise is one shared by all seven artists I interviewed. “It’s always been a part of my technique, leaving the human hand there,” Nova said. “I build the image first as a drawing, generally in graphite but not always, and then I go over it in layers of paint and thin transparent layers of glazing … You still can get that feeling and that energy through the work of the artist who actually made it. It’s a way of transporting yourself and your experience to somebody else. So the flaws are absolutely an essential part of it. You see the process through the flaws.” Nova said she is “high spirited” making art, an experience that Douglass echoes.

“When I’m making a work,” Douglass said, “I’ll come back to it the next day with fresh eyes not having looked at it and I don’t remember doing it. You’re lucky if you get into that flow state where you completely almost blackout … I’ve had a very much out of body experiences in art before where it’s just automatic.”

The artist celebrates imperfections because perfection, the omnipresence of nature or God, is always out of reach. It is an illusion, a different vision for every person, and the ideal we strive towards.

“Perfection is hypothetical,” Parhizi said. “I have a sense of what is good to me, what is beautiful to me, and when I have achieved something. That exact thing, in my mind, I interpret as God or divine. Everybody that takes their art seriously has their own art God, that is satisfied with great work being done.”

Perfection is too big to access: it’s eternity for Douglass, who said it’s the “constant entropy and change of the world,” or reality for Lazar, far more expansive than we each perceive, sacred because it holds meaning. “The sacred element” of art, he said, “lives in the human being’s perception of meaning in the artwork, and that is hopefully what Imperfectionism is going to help cultivate in the viewers.” Reality as such rather than our perception of it, or life as such rather than where it manifests – Washington said “there’s nothing that’s signifying perfection other than life itself.” If not too big to access then perfection is too small to access, a hyper-narrow space that we only glimpse when we experience that sense of meaning.

“There is a little moment,” Nova said, “where you can feel perfection in that space between … seeking and experiencing.”

To better understand imperfection is to better understand perfection. Werner emphasized that Imperfectionism is not a call for sloppy art, nor does it suggest that all art is equally good. It is instead a call to consider the role of chaos in art, not just order, and an artistic practice that aims to find the divine light shining through flaws, a genuine authenticity developed in art and artist. It is a response to an emptiness and lack of emotional connection in the culture. It is the theme of Wönzimer Gallery’s midsummer show, but for the artist’s involved, it is also much more than that.

“This isn’t just a one day, one month long thing,” Washington said. “This is going to be a lifetime of exploring what [Imperfectionism] means in our own work, in our lives … This is going to be a forever movement. This is going to be our lives.”